Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Most abductions end in the safe release of abductees. However, an abduction is by far the most complex and challenging category of crisis that an organisation can face, as it is an ongoing, active event that often involves a great deal of uncertainty and multiple stakeholders with sometimes conflicting priorities.

Note, the term “abduction” can cover various situations in which a person is forcibly taken and held against their will, including:

Detention: Individual is being held lawfully.

Kidnapping: Individual is being held unlawfully and a demand has been made.

Hostage-taking: Individual is being held unlawfully in a known location.

It is vital that organisations pre-identify more than one potential Communicator. Communicators are responsible for passing messages between the Crisis Management Team and the abductors, acting as a buffer. Communicators must be fluent in the predominant local language and require thorough briefing and management.

It is vital that all Communicators fully understand and accept that they are a messenger and therefore do not have any input in or control of the abduction negotiations.

Communicators must be capable of remaining calm and neutral and be resilient, as they may have to listen to threats or violence against abductees. Communicators may be placed in situations where they are required to inform abductors that their demands cannot be met, in scope or timing, and have to listen to the reaction.

Communicators must be patient. They will have little or no opportunity to do any practical task except sit and wait for the phone to ring – hence they should be resilient to stress. They must all be highly trusted and capable to treat all information and decisions in total confidence.

Actors with a vested interest in an abduction case can be numerous and diverse. It is important to understand and monitor their varying motives and concerns, especially as these may change during a crisis, or additional actors may emerge.

Depending on the duration of a crisis, stakeholders can become increasingly challenging to “manage”.

The extent to which host governments become actively involved in the management of an abduction incident naturally differs from country to country. Key factors determining the reaction of a host government may include national law and order infrastructure and enforcement capacity, the degree of political pressure exerted at the international level (by the UN, national governments of abductees or us) and domestic political considerations.

Whilst host governments can act as a valuable source of information, support and advice, their objectives may differ from those of the organisation involved (i.e. safe release of the abductees). This may lead to a lack of support or even hindrance of organisational efforts. Host governments may:

Show greater interest in capturing abductors, thereby deterring future abductions and influencing outcomes.

Wish to be perceived as remaining in control of law and order.

Distrust an organisation’s crisis management capacity and/or resent the fact that an organisation “allowed” an abduction to occur in the first place.

Particularly in high-threat countries, it is advisable for country offices to examine the host government’s reaction to and role in previous abduction cases and establish contact with relevant authorities and law enforcement agencies in advance to understand their likely strategies and response capabilities.

The involvement of the home government of the abductees also hinges on numerous factors. Some governments will pursue a highly proactive approach when their nationals are abducted abroad, while others will adopt a more passive stance if they are confident in the abduction management capacity of the organisation. Additionally, governments will have differing positions on the payment of ransom.

In such instances, the home government may still provide support on request. The home government’s confidence in the organisation concerned will be shaped in part by the abductee’s family. Where a family loses faith in an organisation’s crisis management capacity and strategy, for example, they may press a home government to assume leadership of the situation. Political relations with and strategic interests in the country concerned can also influence governmental attitudes and strategies.

Registration of international individuals with the respective embassies should be completed immediately on arrival to the country, as it likely facilitates co-operation with the embassy in case of an abduction. Countries that do not have any diplomatic representation in-country are usually represented by another nation’s embassy. Moreover, embassies are also often a good starting point for general information regarding which government departments to contact in the event of abduction.

Abduction negotiations require a high level of professional experience and skill. Thus, we may consider (and may be required by our insurance companies) to engage external support from professional response teams. Such services are provided by, among others, independent consultants, private security companies and insurance companies offering kidnap, ransom and extortion or crisis response insurance.

Important criteria for selecting external assistance are the company’s:

Record and expertise in abduction case management and negotiations

Availability for swift deployment

Knowledge of the local context

The selected company should be required to maintain detailed records for post-incident review and potential auditing. It is, however, crucial that we retain overall responsibility and decision-making for the abduction management, even if external assistance is sought. Regardless of whether another actor takes a lead in the abduction management, we must always maintain full influence over decision-making to ensure that we maintain our Duty of Care.

Due to the nature of their mandate, the ICRC usually has a more extensive network, including senior-level contacts that could be leveraged.

Contact with relevant international and national NGOs should be sought. Some may have managed abduction incidents in the country before and may have learned about local networks and mechanisms for managing such incidents.

An independent charity that provides practical and emotional support to families during the kidnap of a loved one and to hostages who have returned home.4

The UN may be able to facilitate access to senior government officials. If UN peacekeepers or others with an armed protection mandate are present, they may well have direct oversight of national civil services, particularly anti-extortion units.

On a local level, community, political and religious leaders may be vital contacts in the management of an abduction incident. Other potentially useful contacts include businesspeople, armed opposition groups and organised criminal groups.

It is assumed that any information existing outside of the Crisis Management Teams will quickly reach the public domain. Communications will only be shared only after the approval of the Crisis Management Team’s Leads. Abduction management requires a high degree of confidentiality. If details of a case become public, the risk of opportunists attempting to exploit the situation, or of damaging leakages to the media, may be increased. The process of establishing and maintaining relationships of trust with perpetrators, family members and abductee’s home government may also be compromised.

Organisations should aim to limit all communication about abductions as much as possible. The Crisis Management Teams operates confidentially and communication to the wider organisation is strictly managed. However, there is a moral duty to update employees. Demands for the latest information can be distracting – employees will be genuinely concerned, yet their claim for more information can distract or paralyse efforts to secure the safe release of the abductees. To guard against this dynamic, internal communications should be delivered at an agreed and regular frequency and employees informed about a nominated internal contact (usually the Media/Comms or Human Resources role on the Crisis Management Team).

Increased public exposure may render it more difficult to control the crisis and potentially lead the abductors to make impossible demands. It is important to consider how, in different scenarios, the news of abduction may spread or can be controlled. It should be agreed who should be informed proactively (and how we will inform them). The timing and content of the information must be determined in consultation with and approved by the Crisis Management Team Leads. External contacts to consider communicating with include:

Families

Donors

Local and national authorities

You should maintain a list of statements in anticipation of an abduction affecting employees. A key example statement is shown below. This statement should be pre-translated into the predominant languages of all country programmes with an abduction risk rated (by an external risk portal) as either HIGH or VERY HIGH. In the event of any incident, limited time will be available to prepare accurate translations, for example, if the news of abduction is in the media before you hear about it from other sources.

We confirm that an employee has been abducted in [insert name of country]. In the interests of their safety, we are not able to comment further at this stage. We are in close contact with their family and are working closely to ensure that everything possible is being done to bring about their safe return.

You should not normally issue any other specific details regarding abductions. However, there may be exceptional circumstances (e.g. when the family or a government has already gone public), in which case you may react differently and make the abduction highly visible in public media.

The role of the Media/Comms role on the Crisis Management Team is to present a positive message about your organisation, emphasising your neutrality and impact in the hope that this may encourage people aware of the abduction to assist you and present information or support leading to a positive outcome. The Media/Comms role will also monitor media coverage, especially if media are in contact with the abductors. The Media/Comms role will also correct any dis/misinformation or negative information that might damage our ability to handle the crisis.

In addition to internal and external communications, other more sensitive communication dictates a confidential and reliable means, both technically and in the management of communications, including:

Dedicated, secure (satellite) phones and voice recorders

Use of codes

Translation (e.g., who will translate sensitive calls).

In addition to the clear psychological impact on the abductees and their families, the impact on colleagues and the Crisis Management Team can be considerable in abduction cases. Thus, you should seek to help these Individuals with psychological support.

You might suspend a country’s activities when abduction occurs. However, this may not be a permanently sustainable situation. Therefore, prior to making any programme decisions, the Crisis Management Teams should consider the following.

Does suspension or continuation of activities increase the possibility of opening communication channels with the abductors? What are the implications of suspension or continuation of the activities regarding community support?

What are the implications of the abduction for the risk assessment of the country programme?

The crisis will likely require the full-time attention of some of the Crisis Management Team members. Which programme activities can be continued with the remaining management capacity?

It is suggested that in the initial reaction to a (suspected) abduction, decisions beyond suspension are avoided except those necessary to ensure the immediate safety of remaining employees. Until further details emerge, and we can reasonably judge what threat exists towards remaining employees, they should be placed in the most secure situation that can be immediately achieved (e.g. hibernation). It should be noted that continuation or the partial continuation of activities may be either positive or negative factors for our negotiations with abductors.

The following organisations provide useful resources:

Hostage UK:

Disclaimer: To the fullest extent permitted by law, Open Briefing will not be liable for any loss, damage or inconvenience arising as a consequence of any use or misuse of this resource.

Copyright © Open Briefing Ltd, 2020. Some rights reserved. Licensed under a .

Wish to prevent organisations from interacting with “terrorists” or “rebels” for political reasons.

Impose legislation prohibiting any or all forms of contact with abductors.

Agencies (UN, ICRC, NGOs)

Security networks (e.g. INSO, GISF, UNDSS)

Media (national and international)

Local communities and beneficiaries.

Global Interagency Security Forum (GISF):

Safeguarding means:

Taking all reasonable steps to prevent harm, particularly sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment.

Protecting people, especially at-risk adults and children, from that harm.

Responding appropriately when harm does occur.

It also means protecting staff from any forms of bullying, harassment, sexual harassment, discrimination and abuse of power.

Child protection is an element of safeguarding and promoting welfare. It refers to the activity that is undertaken to protect specific children who are suffering or likely to suffer significant harm.

Child abuse is defined as all forms of physical abuse, emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse and exploitation, neglect or negligent treatment, commercial or other exploitation of a person below the age of 18, including any actions that result in actual or potential harm. Abuse can happen anywhere and at any time, but research shows that the perpetrators of abuse are likely to be known and trusted by the child. The most commonly defined types of abuse are:

Violence towards or deliberate injury of a child.

Using a child for sexual stimulation or gratification.

Behaviour that harms a child’s self-esteem.

Children in exploitative situations and relationships may receive gifts, money or affection as a result of performing sexual activities or others performing sexual activities on them.

An at-risk adult is a person who may need care by reason of mental or other disability, age or illness, and who is or may be unable to take care of him or herself, or unable to protect him or herself against significant harm or exploitation.

At-risk adult abuse can take many forms, including physical, sexual, psychological, financial/material, discriminatory and domestic abuse and self-neglect.

When a person purposefully injures or threatens to injure an at-risk adult. This includes (but is not limited to) hitting, slapping, pushing, kicking, misusing medication and applying unlawful or inappropriate restraint and inappropriate physical sanctions.

Unwanted sexual activity or behaviour that happens without consent or understanding.

Emotional abuse that causes distress and can be verbal and non-verbal. Includes humiliating and degrading treatment such as name calling, constant criticism, belittling, persistent shaming, solitary confinement and isolation.

Includes theft, fraud, exploitation and pressure in connection to wills, property, inheritance and financial transactions, or inciting an at-risk adult to do any of these things on another individual’s behalf; it may also involve the misuse or misappropriation of property, possessions and benefits of an at-risk adult.

Includes a wide range of behaviours such as the failure to provide an at-risk adult with the conditions that are culturally accepted as being essential for their physical and emotional development and well-being. Self-neglect related to the failure to care for one’s own personal hygiene or health.

Refers to any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive or threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are, or have been, intimate partners or family members, regardless of gender or sexuality.

Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (PSEA) is a term used by the humanitarian and development community to refer to the prevention of sexual exploitation and abuse of affected populations by staff or associated personnel.

The term is derived from the .

The term ‘sexual exploitation’ refers to any actual or attempted abuse of a position of vulnerability, differential power or trust for sexual purposes, including, but not limited to, profiting monetarily, socially or politically from the sexual exploitation of another. This definition incudes human trafficking and modern slavery.

The term ‘sexual abuse’ refers to an actual or threatened physical intrusion of a sexual nature, whether by force or under unequal or coercive conditions.

Sexual violence refers to:

Any sexual act or attempt to obtain a sexual act.

Unwanted sexual comments or advances or acts to traffic that are directed against a person’s sexuality, involving coercion by anyone, regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting, including at home and at work.

Three types of sexual violence are commonly distinguished:

Sexual violence involving intercourse (i.e. rape).

Contact sexual violence (i.e. unwanted touching, but excluding intercourse).

Non-contact sexual violence (i.e. threatened sexual violence, exhibitionism and verbal sexual harassment).

While coerced sex may result in sexual gratification for the perpetrator, its underlying purpose is to express power and dominance over the other person.

Grooming is behaviour that an offender uses online or in the real world to procure sexual activity from a child. It can include building trust with children and/or their carers to gain access to children to sexually abuse them.

Coercion covers a whole spectrum of degrees of force. Apart from physical force, it may involve psychological intimidation, blackmail or other threats. These include, for instance, threats of being dismissed from a job or of not obtaining a job that is sought. It may also occur when a person is unable to give consent, for example, while drunk, drugged or asleep or is mentally incapable of understanding the situation.

The custom of marrying young children, particularly girls, is a form of sexual violence, as children are unable to give or withhold consent.

Slavery is a situation where a person exercises (perceived) power of ownership over another person. Related terms include ‘forced labour’, which covers work or services that people are not doing voluntarily but under threat of punishment; ‘human trafficking’, which involves deceptive recruitment and coercion; and ‘bonded labour’, which is demanded in repayment of a debt or loan. Modern slavery encompasses a spectrum of labour exploitation, ranging from the mistreatment of vulnerable workers and human trafficking to child labour and forced sexual exploitation.

This refers to the person who has been abused or exploited. The term ‘survivor’ is often used in preference to ‘victim’ as it implies strength, resilience and the capacity to survive. However, how they wish to identify themselves is the individual’s choice.

Bullying is the intimidation or belittling of someone through the misuse of power or position, which leaves the recipient feeling hurt, upset, vulnerable or helpless. It is often inextricably linked to the areas of harassment described above. The following are examples of bullying:

Levelling unjustified criticism of an individual’s personal or professional performance, shouting at an individual and/or criticising an individual in front of others.

Spreading malicious rumours or making malicious allegations.

Intimidating or ridiculing individuals with disabilities and/or learning difficulties.

Harassment is generally described as unwanted conduct that affects the dignity of women or men at work, that takes place both within the office and off-site at places such as clinics, conferences and meetings. It encompasses unwelcome physical, verbal or non-verbal behaviour that denigrates or ridicules or is intimidatory. The essential characteristic of harassment is that the action is unwanted by the recipient.

Harassment can take many forms. It may be directed in particular against women and ethnic minorities or towards people because of their age, disability, gender/gender reassignment, marriage/civil partnership, pregnancy status, fertility status, race, religion or belief, sex, or sexual orientation or because of them being part of any other protected class. It may involve any action, behaviour, comment or physical contact that is found to be objectionable or that causes offence. It can result in the recipient feeling threatened, humiliated or patronised, and it can create an intimidating work environment.

Examples of prohibited harassment can include but are not limited to the following:

Cartoons or other visual displays of objects, pictures, or posters that depict protected groups in a derogatory way

Verbal conduct, including making derogatory comments or jokes or using epithets or slurs towards such groups.

The definition of sexual harassment includes ‘unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favours, and other conduct that creates a coercive, hostile, intimidating, or offensive work environment’. The harassment of a sexual nature may be directed at a person of the same or opposite sex.

The key elements of this harassment are that the behaviour is uninvited, unreciprocated and unwelcome and causes the person involved to feel threatened, humiliated, or embarrassed. The behaviour may also be determined to be sexual violence and harassment if:

Submission to such conduct is explicitly or implicitly made a term or condition of employment.

Submission to or rejection of this conduct is used as a basis for an employment decision, thereby affecting the staff member.

Such conduct has the purpose or effect of substantially interfering with an individual’s work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile or offensive work environment.

Some examples of sexual harassment can include:

Excessive, one-sided, romantic attention in the form of requests for dates, love letters, telephone calls, emails or gifts.

Unwelcome sexual advances, such as requests for dates or propositions for sexual favours, whether or not they involve physical touching. This may include an expression of sexual interest after being informed that the interest is unwelcome or in case of a situation that began as reciprocal attraction but later ceased to be reciprocal.

Offering employment benefits in exchange for sexual favours.

In the workplace, racial or sectarian harassment may take the form of actual or threatened physical abuse, or it may involve offensive jokes, verbal abuse, language, graffiti or literature of a racist or sectarian nature or offensive remarks about a person's skin colour, physical characteristics or religion. It may also include repeated exclusion of a person from an ethnic or religious minority from conversations, patronising remarks, unfair allocation of work or pressure about the speed and/or quality of their work in a way that differs from the treatment of other staff members.

This refers to any unfair treatment or arbitrary distinction based on a person's race, sex, religion, nationality, ethnic origin, sexual orientation, disability, age, language, pregnancy status, fertility status, social origin or because of them being part of any other protected class. Discrimination may be an isolated event affecting one person or a group of persons similarly situated or may manifest itself through harassment or abuse of authority.

Disclaimer: To the fullest extent permitted by law, Open Briefing will not be liable for any loss, damage or inconvenience arising as a consequence of any use or misuse of this resource.

Copyright © Open Briefing Ltd, 2020. Some rights reserved. Licensed under a .

Ignoring or excluding an individual from the team/group.

Unwelcome leering, whistling, brushing against the body, sexual gestures, suggestive comments, staring, sexual flirtation or proposition.

Displaying a sexually suggestive object in the workplace or telling or making sexual jokes, stories, drawings, pictures or gestures.

Creating or repeating a sexually related rumour about another staff member.

Making an inquiry into a staff or associate’s sexual experiences.

Reprisal or making a threat after a negative response is made to a sexual advance.

Unwelcome physical contact, including pats, hugs, brushes, touches, shoulder rubs, assaults, or impeding or blocking movements.

Physical assault, such as rape, sexual battery, an attempt to commit an assault, or intentional physical conduct, such as:

Impeding or blocking movement.

Touching or brushing against the body of another staff member.

Making a derogatory comment or joke regarding an individual’s sexual orientation or perceived sexual orientation.

Making sexual comments about someone’s looks or clothes.

This knowledge base will help you adapt the policies, procedures, and resources provided by Frontline Policies. It is vital that your organisation does this to reflect its specific profile, ways of working, and location. This process should involve a wide range of co-workers and other stakeholders in your organisation.

We have de-mystified the language and methodology of security risk management throughout Frontline Policies. Nonetheless, some elements of the security framework can be complex and need to be carefully thought through. If you need help, please request support from Open Briefing.

This project was made possible thanks to the support of the and .

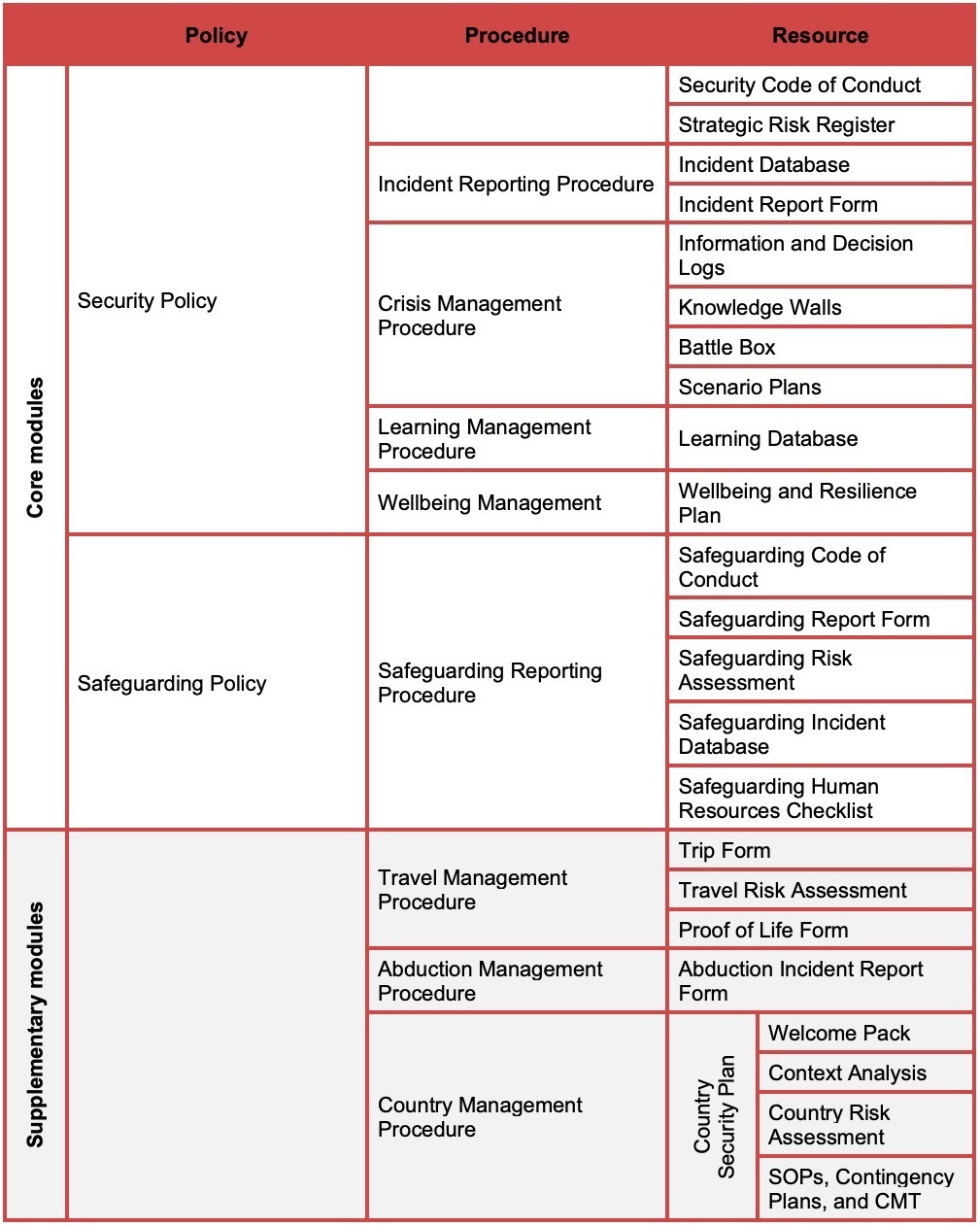

The security risk management frameworks built by Frontline Policies consist of policies, procedures, and resources. These three types of documents differ in important ways:

Policies identify the legal and moral responsibilities and commitments that organisations have and the ways that we will manage them in a systematic way.

Procedures detail how we will achieve the commitments made in the policy.

Resources are the forms and other tools that we use to implement the procedures.

Your framework will consist of seven Core Modules made up of two policies and five procedures plus a number of resources. You may also have up to three Supplementary Modules depending on the answers that you provided in Frontline Policies.

Unless stated otherwise in this guidance, you should amend each section of the framework to better fit your organisation's profile, ways of working, and location.

In order to continue to meet best practice and reflect any changes in applicable law, you should also review each procedure at least once every two years.

Decisions about security risk management are made by and affect people. Two categories of people are integral to the approach taken in Frontline Policies:

‘A Senior Person’. It is important that decisions with respect to security risks are taken by a suitable people in your organisation. Throughout the policies, procedures, and resources, many decisions are allocated to a ‘Senior Person’. When adapting the documents, we recommend that you replace this text with the title of an appropriate role within your organisation, such as the executive director or other senior manager.

‘Those who work on our behalf’. While there may be specific things that your organisation needs to do to meet its legal duty of care obligations for employees, it may be less clear for consultants, volunteers and others who you work with. There may be donor requirements or contractual obligations, but it is largely your organisation’s moral choice regarding what you want to provide for non-employees. Therefore, you may choose that some policies, procedures, or resources only apply to employees (e.g. learning management procedure), while others may apply to employees, contractors, consultants, volunteers, suppliers, and any others who work on your organisation’s behalf (e.g. Safeguarding Policy).

Purpose: In the Security Policy, your organisation accepts its duty of care obligations; identifies its risk appetite, strategies, and principles; details its risk management responsibilities, duty bearer commitments, and crisis management commitments; and sets out its risk management methodology.

This section is an important accountability statement. It states that your organisation has a duty of care (legal, moral or contractual) and recognises this as an obligation. It also states that your organisation seeks to reduce risk and effectively respond to incidents.

This section states that any failure to follow the Security Policy and the other elements of the security framework will be considered a disciplinary matter, which may result in disciplinary action up to and including termination of contract. This is included to allow your organisation to act when those who work on your behalf refuse to follow your organisation’s security risk management procedures and all other forms of encouragement and training have failed.

This is a critical section of the Security Policy. Your organisation’s risk appetite needs to be confirmed and communicated so that your organisation can achieve the following:

Meet best practice (and in some cases legal requirements)

Provide clear parameters for your co-workers

Systematically assess and manage risk

Your organisation’s risk appetite must be as follows:

Measurable. This is achieved through risk registers and risk assessments.

Related to capacity. The higher your risk appetite, the higher must be your capacity to manage and respond to risks.

Integrated with control mechanisms. This is achieved through the strategies and mitigations applied in your risk registers and risk assessments.

To help you structure your risk appetite statement, it has been broken down into the three sections described below:

Risk appetite statement. This section identifies why your organisation and co-workers are exposed to risk and indicates your primary risk management approach (you can choose to avoid, manage, transfer, or accept risk). It further states that your organisation uses a systematic risk management methodology and indicates the level of risk above which you are not willing to go (you can choose VERY LOW, LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH, or VERY HIGH).

Operating above our risk appetite. This section describes how your organisation approaches ‘criticality’. This sets out that your organisation may, on occasion and for good reason, accept risks higher than those stated above. If it is possible that your organisation will do this, then you need to detail the factors that will be considered and whose approval will be required for the final decision.

If you indicated that you either operate in or travel to hostile environments, your policy will also include a ‘Risk Ratings’ and ‘Minimum Standards’ section, which relate to your Travel Management Procedure and/or Country Management Procedure.

Your organisation should approach the management of security risks with a set of principles. You may wish to develop your own principles and/or remove some of the suggested ones; however, we would strongly advise against removing ‘Primacy of Life’ and ‘Freely Decline’ as these specifically relate to common legal requirements.

Different organisations will need to adopt different security risk management strategies to ensure risk reduction in appropriate ways. Organisations may also prefer to adopt a ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ approach to managing security risks. Commonly, in rights-based or humanitarian organisations, softer strategies like low profile and network leverage are preferred over harder strategies like armed deterrence or close protection.

In this table, you can remove or add to the example strategies provided. We strongly advise that you indicate a most preferred and least preferred strategy. Some organisations may wish to add a specific sentence to indicate that the use of weapons – armed deterrence – is not allowed (unless under specific circumstances, if agreed, when they must be approved by a Senior Person).

This section details who is responsible for which security risk management tasks. These responsibilities have been split as follows:

Risk owners. Those accountable and responsible for the risk in your organisation.

Risk managers. Those who operationally manage the risk in your organisation.

Risk exposed. All those who work on your behalf.

Please review and add or delete the responsibilities for the risk owners, managers, and exposed so that they are appropriate to your organisation. For the risk owners and risk managers, please indicate the role of the person responsible, e.g. executive director.

This section details what commitments you make to each ‘duty bearer’ in your organisation. A duty bearer is a category of people for whom you have a duty of care; examples might include employees, consultants, volunteers, and suppliers. You may want to use different, more specific categories, such as international employees, national employees, long-term contractors, short-term consultants, volunteers, consortium partners, implementing partners, and suppliers.

To complete this section, do the following:

Decide who your duty bearers are and enter them into the columns in the top right.

Review the commitments under each section (security governance, travel and crisis management, partners, and donors), amending commitments to fit your organisation, work, and location.

Adjust the checkmarks to ensure that each duty bearer has been assigned the correct commitments.

An individual’s exposure to risk depends on the interaction between multiple factors, such as follows:

Individual (e.g. ethnicity, gender, sexual identity)

Organisational (e.g. seniority of role, activities of your organisation)

Operational (e.g. role purpose, access to sensitive information)

Some individuals who work on your behalf will have increased exposure (vulnerability) to risk as a result of one or more of these factors. As such, it is not enough to apply a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to security risk management. In your risk assessments and security risk management practices, your organisation needs to identify the above-mentioned factors and implement mitigations to reduce the risk for all people who work on your behalf but particularly those who have increased exposure to risk. Please amend the table to further tailor your Security Policy.

This section details (depending on your answers) your organisation’s policy approach to domestic relocation and international evacuation for security and medical reasons. Please review this section and amend as appropriate.

This annex to the Security Policy details your risk management methodology in four phases:

Phase 1 – Context

Phase 2 – Assess

Phase 3 – Control

You may wish to adapt this section to make it more relevant to your organisation, work, and location; however, any updates will also need to be reflected in other documents in the framework (e.g. Strategic Risk Register and risk assessments).

Purpose: The Security Code of Conduct codifies the security-related behaviours that those working on your behalf must understand and follow.

It is split into two sections:

Background. Why the Security Code of Conduct is important and the consequences of not following it.

Agreement. What those who work on your behalf agree to by signing the document.

Please work through the agreement section and amend as appropriate. Once you have a final version in place, it should be signed by all those who work on your behalf and integrated into recruitment and contracting processes.

Purpose: Strategic risks are those that are likely to affect your entire organisation rather than an individual staff member. This might include reputational damage, legal action, major fraud, and so on. The Strategic Risk Register is used to record these threats, your assessment of the risk that they pose, and the mitigations in place to reduce the risk. As the Risk Register is for risks at a strategic level, it should be completed by the Senior Person or Senior Management Team and reviewed regularly (ideally quarterly).

To complete the Strategic Risk Register, follow these steps:

List the threats that could harm your organisation and describe why your organisation is vulnerable (exposed) to each threat.

Look at the Scoring Definitions tab to decide likelihood and impact scores (without implementing any mitigations) and enter either 1 (VERY LOW), 2 (LOW), 3 (MEDIUM), 4 (HIGH) or 5 (VERY HIGH) for each using the dropdown.

Identify measures already in place to reduce the likelihood and impact of your organisation being harmed. Focus on reducing your organisation’s vulnerabilities (exposure).

Purpose: The Incident Reporting Procedure identifies why incidents should be reported, defines what an incident is, outlines the four steps of incident reporting, and discusses the Incident Database. (Note, this procedure is not for reporting safeguarding incidents, which should be reported under the Safeguarding Reporting Procedure.)

All security incidents and near misses that involve anyone working on your behalf should be reported to a Senior Person. This is important because it:

Ensures that immediate support can be provided to the affected individual(s) to reduce any remaining risks to them or others.

Allows you to identify any trends or patterns of incidents you are exposed to and to determine whether any remedial action to prevent the reoccurrence of similar incidents is warranted or whether the security environment is deteriorating or improving.

Provides you with a measurable indicator of whether existing policies and procedures are sufficiently reducing risk or whether alternative approaches need to be explored.

Please review this section and amend as appropriate, including any additional ‘incident affected’ categories to ensure that you include all the incidents that your organisation would like to be reported. Please remember that this procedure does not include the reporting of safeguarding incidents which should be reported under the Safeguarding Reporting Procedure.

This section sets out the incident reporting process in four phases: immediate verbal report, written report, incident review, and incident follow-up. You may want to include an additional phase, incident escalation, between immediate verbal report and written report if yours is a large organisation or if it would like additional managers to be informed of all incidents. Please review this section and amend as appropriate, including changing the Senior Person to a role or roles in your organisation.

Please review this section and amend as appropriate, including changing the Senior Person to a role or roles in your organisation.

Purpose: The Incident Database allows your organisation to identify any trends or patterns of incidents to determine whether any remedial action is required to prevent future reoccurrence of similar incidents and to provide a measurable indicator of whether existing policies and practices are sufficiently reducing risk.

The Incident Database should regularly feed into the (ideally quarterly) review of the Strategic Risk Register on which safety and security should be a standing risk.

Purpose: The Incident Report Form should be used for all incidents (after the immediate verbal report). Each written incident report should outline in some detail what happened and when and how those involved responded. Please ask the affected person to work through all sections of the incident report.

Once an Incident Report Form is submitted, it should be reviewed and entered into the Incident Database and used as the basis for the incident review and incident follow-up process.

Purpose: The Crisis Management Procedure defines what a crisis is, outlines the composition of your crisis management team (CMT) and their roles and responsibilities, confirms when a crisis management team should be activated, and provides actions for each phase of a crisis response. This document can be used by both your global CMT and any country CMTs.

This paragraph provides a definition of a crisis as set out below. You may wish to amend this definition to better describe the things that could cause critical harm to your people or organisation.

An unexpected event or situation that has caused, or has the potential to cause, critical harm to our people, reputation, finances, systems, projects or entire organisation, and thus requires a dedicated crisis management team to manage its impact and aftermath.

A robust CMT includes a range of functions because several different skillsets are required to effectively reduce the impact of a crisis. You may wish to adapt the proposed structure to better fit your organisation, work, and location; however, the following roles are considered critical: Lead, Support, Human Resources, Family Liaison, Media/Communications, and Administration. It is essential that CMT members are selected based on their relevant skills, experience, and personality rather than seniority.

You should activate a CMT when an incident meeting your definition of a crisis occurs. To help operationalise this definition, it is useful to have a set of ‘activation triggers’ that automatically activate the team. These have been listed in this section of the Crisis Management Procedure. You may wish to amend these triggers to better fit your organisation, work, and location. However, activating a CMT should not be only considered as a ‘last resort’. When there are uncertainties, it is preferable to activate a CMT and then stand it down if not required rather than letting a situation continue until it has definitely reached the threshold of your organisation’s definition of a crisis.

This section identifies the phased approach to managing a crisis. It is based on crisis management best practice.

This section assigns specific actions to CMT members at each phase of a crisis. You may wish to amend the specific actions or who they are assigned to as suitable for your organisation, work, and location.

Purpose: The Information and Decision Logs are used throughout a crisis to log the incoming information, outgoing information, and major decisions taken.

The logs are helpful for several reasons, including the following:

Keeping track of what has happened and at what time.

Reminding CMT members of tasks that need to be completed.

Communicating to other CMT members all the information sent and received and decisions taken so that they have a full picture of the response.

Purpose: The Knowledge Walls are used as one-page visual aids. They remind CMT members of the initial and current situation and provide an essential live record of the crisis response priorities, including the final objective.

Purpose: Your organisation should always maintain a Battle Box, containing the resources and equipment in this list. This saves valuable time when a CMT is activated as the box can be opened and a crisis room set up rapidly without having to locate the required items.

Purpose: The Scenario Plan is a template that the CMT members can use to identify future scenarios in a crisis (best, worst, and most likely outcomes).

Regularly completing the Scenario Plan allows the team to develop pre-defined responses, understand factors that can be controlled and influenced, and understand what resources are required to respond. This significantly helps the CMT get ahead of the situation and reduce the number of surprises that can emerge in any crisis.

Purpose: The Learning Management Procedure details your risk-based learning principles and presents the learning programme available for those working on your behalf based on their role and the level of risk that to which they are potentially exposed.

This section identifies the key principles and practices to which your organisation commits. You may wish to adapt these to better fit your organisation, work, and location.

This section details the required learning, based on each person’s role and the level of risk to which they are potentially exposed. It also details the required frequency of refresher training. While the training identified in this table is based on best practice, you may wish to amend the roles, learning requirements, and required frequency in order to better fit your organisation, work, and location.

This section provides a description and duration for each course identified in the learning programme. You may wish to adapt the description and duration (which are based on best practice) particularly if you adapted the learning programme.

Please indicate the person that should be contacted to discuss learning requirements and course access.

Purpose: The Learning Database allows your organisation to record important training information so that you know who has completed what courses when, where, and with what provider and when a refresher course is due. This information will help you to plan when to run training courses and to check if people meet the requirements for specific activities such as travel.

If you amended the courses available in your organisation’s learning programme, you will also need to amend the reference table tab.

Purpose: The Wellbeing Management Procedure details your organisation’s wellbeing principles and presents the physical and psychological health support that you have made available to those working on your behalf.

This section identifies the key principles and practices to which your organisation commits. You may wish to amend the principles and practices in order to better fit your organisation, work, and location.

This section explains the information provided to potential employees. It is a crucial part of gaining informed consent to provide potential employees with an indication of the stressors and risks that they may face during their employment and as part of their role.

In addition, this section states that your organisation will ask potential employees about how they will manage their wellbeing, so that your organisation and the candidate have the opportunity to discuss the candidate’s ability to manage stress. If you agree to adopt this process, it must be on the basis that it is a helpful conversation that is focussed on identifying any additional support needs that a candidate may have. It is vital that this process does not affect a candidate’s chances of employment, and this should be made very clear to all candidates.

This section explains the access to health and wellbeing resources, training, and psychological support that employees are provided with during their employment.

The support outlined is extensive so it is important to adapt this section to better fit your organisation, work, and location. Please do not include anything in this section that you feel would not be possible to provide to all your employees.

This section outlines employees’ access to a wellbeing debrief (at the end of their employment) and psychological support (after their employment).

It is important to adapt this section to better fit your organisation, work, and location. Please do not include anything that you feel would not be possible to provide to all your employees.

Please include the contact details of the person who employees should contact to discuss access to wellbeing support. If you have an Employee Assistance Provider or wellbeing provider, you should include their information here as well.

Purpose: The Wellbeing and Resilience Plan is a useful resource for employees and others who work on your behalf. It presents different zones of stress, asking individuals to identify their own personal indicators of stress and strategies to help them get back on track during stressful periods of their lives.

It is important that the plan not be shared, unless the individual completing it chooses to do so. The Wellbeing and Resilience Plan is a confidential document, and organisations must not ask individuals to share them.

There should be no need to amend this plan as it applies to all organisations.

Purpose: Safeguarding is the responsibility that your organisation has to ensure that staff, operations, and programmes do no harm to children and at-risk adults, particularly in relation to sexual exploitation and abuse. It also entails protecting your staff from bullying, harassment, and discrimination. The Safeguarding Policy details how your organisation achieves these safeguarding obligations. It outlines a clear policy as well as internal and external facilities to disclose safeguarding concerns through the safeguarding reporting system or anonymously through the whistleblowing process.

This section states that your organisation has a duty to provide safeguarding standards and to take reasonable steps to mitigate any foreseeable harm. It also states that the Safeguarding Policy is designed to protect both children and at-risk adults.

This section clarifies that the consequences of not following the safeguarding framework is considered a disciplinary matter and may result in disciplinary action up to and including termination of contract. This is included to allow your organisation to act when those working on your behalf refuse to follow your organisation’s safeguarding procedures.

This section clarifies that the document is underpinned by overarching principles that are informed by the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and safeguarding best practice. If you do not significantly change the contents of the Safeguarding Policy, you need not amend this section.

This section details who is responsible for which safeguarding tasks. These responsibilities have been split into different common roles. Please amend the responsibilities so that they are appropriate to your organisation, indicating who is responsible.

This section details and distinguishes the (external) whistleblowing and (internal) reporting procedures. Whistleblowing should only take place if those who have concerns honestly believe that it is in the public interest to use the whistleblowing process. Otherwise, the reporting procedure should be used. Please add the email and phone number for the person in your organisation that staff with safeguarding concerns should report to if it is not reasonable for them to speak to their line manager. You may wish to adapt the whistleblowing and reporting procedures in order to better fit your organisation, work, and location.

This section details the safeguarding considerations that your organisation should integrate into its recruitment process. This includes job profiles, job advertisements, interviews, reference checks, proof of identification and qualifications, criminal records check and security clearance, a code of conduct, probationary periods, inductions, and training. You may wish to adapt the human resources section to better fit your organisation, work, and location.

This section details the key elements of the safeguarding risk assessment and risk reduction measures implemented by your organisation, including ensuring that all partners complete a safeguarding due diligence assessment. You may wish to adapt this section to better fit your organisation, work, and location.

This section details the commitments that your organisation and those working on your behalf implement when working with children and at-risk adults. This includes safeguarding children and at-risk adults, protection from sexual exploitation and abuse, protection from bullying, harassment, sexual harassment, discrimination and abuse of power, and a code of conduct. You may wish to amend the code of conduct section to better fit your organisation, work, and location.

This section details how those who work on your behalf can make a complaint or raise a concern and how complaints and concerns are handled. It lays down the confidentiality around complaints and concerns; the action that will be taken against anyone retaliating against complainants, survivors, and witnesses; and your organisation’s approach to supporting survivors. You may wish to adapt the reporting section to better fit your organisation, work, and location.

See the for more information.

Purpose: The Safeguarding Reporting Procedure details how your organisation approaches reporting and handling safeguarding complaints and concerns.

This section details your organisation’s goal of prevention; defines what a safeguarding complaint or concern is and explains why those who work on your behalf need to report them; describes how one can make a report and what happens after a report is made; explains your organisation’s approach to confidentiality around safeguarding; details action taken in situations of retaliation against complainants, survivors, and witnesses; and outlines the survivor-centred approach. You may wish to adapt the reporting principles section to better fit your organisation, work, and location.

This section details who to make a report to. Please enter the name of your Safeguarding Focal Point or other person responsible for receiving reports.

This section details how your organisation handles complaints and concerns, the decision-making process that the Safeguarding Committee will follow, the Safeguarding Committee’s composition, the investigation process, how your organisation will determine whether an investigation is warranted, and how referrals are made to national authorities for prosecution (where the conduct is a criminal act). You may wish to adapt the decision-making and investigations section to better fit your organisation, work, and location. However, we recommend that you make as few adjustments as possible in order to remain aligned with best practice.

This section details the extent of possible disciplinary actions and outlines the grievance procedure that can be followed by persons reporting the concern if they are not satisfied with the handling of the concern. You may wish to adapt the disciplinary process section to better fit your organisation, work, and location.

This section details how incidents are reviewed and followed up. You may wish to adapt the disciplinary process section to better fit your organisation, work, and location.

Purpose: The Safeguarding Code of Conduct sets out the safeguarding-related behaviours that those working on your behalf must understand and follow.

The Code is divided into two sections:

Background. Why the Safeguarding Code of Conduct is important and the consequences of not following it.

Agreement. What those who work on your behalf agree to by signing the document.

Please work through the agreement section and amend as appropriate. Once you have a final version in place, it should be signed by all those who work on your behalf and integrated into recruitment and contracting processes.

Purpose: The Safeguarding Report Form is used to report safeguarding concerns. It can be completed by a complainant or on their behalf. The form is also used to record the actions taken following a reported concern.

Purpose: The Safeguarding Risk Assessment outlines how your organisation assesses safeguarding threats and provides a risk assessment tool and recommended safeguarding mitigations.

This section details the three levels of safeguarding risk ratings that are used throughout the document.

This section presents a framework for assessing safeguarding threats based on three criteria and the safeguarding risk ratings.

This section assists the assessment of safeguarding risk and asks the user to allocate a risk rating based on their answers to the questions.

This section presents the recommended mitigations based on the level of assessed risk.

Purpose: The Safeguarding Incident Database allows your organisation to record safeguarding incidents, the outcome of investigations, and details of any follow-up actions. The Safeguarding Incident Database should feed into the (ideally quarterly) review of the Strategic Risk Register on which safeguarding should be a standing risk.

Purpose: The Safeguarding Human Resources Checklist provides a checklist for Human Resources to use before, during, and after employment.

You may wish to adapt the checklist to better fit your organisation, work, and location.

You will only have this procedure and its associated resources if you indicated that people in your organisation travel.

Purpose: The Travel Management Procedure identifies the actions that travellers and managers must take to reduce safety and security risks when travelling for work.

This section provides a diagram that represents the travel journey used throughout the procedure. The travel journey includes the following stages: notify, standards, approve, confirm, travel, and return. While you may wish to adapt the details of the procedure itself, we recommend that you retain the original stages of the travel journey.

This section states that the traveller needs to notify a nominated Travel Manager of their intention to travel well in advance of the planned departure date.

This section details the standards that the traveller and travel manager must ensure are in place prior to the planned departure date. If you indicated that your organisation conducts travel to hostile environments, this section also includes a risk rating and enhanced standards.

This section details how the traveller provides their own consent to travel and who in your organisation approves the traveller’s request. If you indicated that your organisation conducts travel to hostile environments, this section also includes different risk approvers based on the risk rating of the destination.

This section details how the traveller and travel manager should confirm the travel arrangements, following risk and budget approval. Additionally, if you indicated that your organisation conducts travel to hostile environments, this section includes the need for the traveller to attend a pre-travel security briefing.

This section details the check-in process and actions that are taken if the traveller fails to check-in. If you indicated that your organisation conducts travel to hostile environments, this section also includes different check-in times for travel to different risk-rated destinations.

This section details that the traveller must attend an incident review meeting if they were affected by or witnessed an incident. It confirms that the traveller may be able to access continued physical and psychological support in line with your organisation’s offering.

This annex provides further information on the standards that the traveller and travel manager must ensure are in place prior to the planned departure date. If you indicated that your organisation conducts travel to hostile environments, this section also includes enhanced standards. If you have amended any of the travel standards, you will need to amend this section as well.

Purpose: The Trip Form should be completed by the traveller. It contains details of the trip, travellers, activities, flights, accommodation, internal and external contacts, and confirmation that the standards have been met and provides an area for traveller consent and approval.

If you indicated that your organisation conducts travel to hostile environments, the form also includes the Travel Risk Assessment (below) and a contingency plans section that should be completed for travel to HIGH and VERY HIGH risk-rated destinations.

Purpose: If you indicated that your organisation conducts travel to hostile environments, the Travel Risk Assessment should be completed for travel to HIGH and VERY HIGH risk-rated destinations.

To complete the Travel Risk Assessment, follow these steps:

List the potential threats that your travellers could be harmed by and describe why they are vulnerable to each threat.

Look at the Scoring Definitions tab to decide likelihood and impact scores (without implementing any mitigations) and enter either 1 (VERY LOW), 2 (LOW), 3 (MEDIUM), 4 (HIGH) or 5 (VERY HIGH) for each using the dropdown.

Identify measures that can be put in place to reduce the likelihood and impact

Purpose: If you indicated that your organisation conducts travel to hostile environments, the Proof of Life Form should be completed for all travel to HIGH and VERY HIGH risk-rated destinations.

This section explains that Proof of Life is essential in abduction management and fulfils two functions:

Verifies claims by a group that it is holding the abductees or has contact with the group holding them. Proof of Life is vital to distinguish real abductors from opportunists or from groups that may have held the abductees at some point but are no longer holding them.

Confirms that the abductees are still alive.

This section outlines several explicit agreements of which the person completing the Proof of Life Form needs to be aware. If you chose to adapt the form to better fit your organisation, work, and location, you may also need to amend these explicit agreements.

This section confirms that any changes to Proof of Life Forms must be made through the submission of a new form. It is vital that this section remain in the form as Proof of Life Forms should only be accessed in the event of a (confirmed or suspected) abduction or detention and not for any other reason including editing.

This section confirms who in your organisation has access to completed Proof of Life Forms and who may be provided with some or all the information contained within them. You may wish to adapt this section to better fit your organisation, work, and location. However, you should only amend the internal people detailed section and not the disclosure to others one as that is a legal requirement in many countries.

This section details the primary and secondary emergency contacts selected by the person completing the form.

This section asks the traveller to accept and agree with several specific statements. We do not recommend that you amend this section other than where indicated in red.

This section details how your organisation will contact the primary and secondary emergency contacts selected by the person completing the form. We do not recommend that you amend this section.

This section is the first of four sections in which the person completing the form has the option to give or not give consent. In this case, they are asked to consent to sharing their personal medical details with your organisation. If they choose to consent, they are asked to provide relevant information. We do not recommend that you amend this section other than where indicated in red.

Providing abductors and other specified persons with personal medical details may be relevant in identifying and treating them if they become ill or wounded or have a pre-existing medical condition or require medication.

This section is the second of the four sections where the person completing the form has the option to give or not give consent. In this case, they are asked to consent to sharing their phone and debit and credit card details with your organisation. If they choose to consent, they are asked to provide relevant information. We do not recommend that you amend this section other than where indicated in red.

Providing law enforcement or government agencies access to phone and debit and credit card data after an abduction has occurred may provide them with an understanding of when and where these may be used or may provide details of where the individual is held or where persons connected with the abduction are active.

This section is the third of the four sections where the person completing the form has the option to give or not give consent. In this case, they are asked to consent to sharing their social media account details with your organisation. If they choose to consent, they are asked to provide relevant information. We do not recommend that you amend this section other than where indicated in red.

Providing law enforcement or government agencies access to social media accounts after an abduction has occurred may allow them to suspend their accounts to limit their usefulness to the abductors and limit media intrusion (e.g. accessing photos or contacting family members or friends).

This section is the last of the four sections where the person completing the form has the option to give or not give consent. In this case, they are asked to consent to sharing their photographic representation with your organisation. If they choose to consent, they are asked to provide relevant information. We do not recommend that you amend this section other than where indicated in red.

This section is where the person completing the form enters five Proof of Life questions and answers, considering the following:

They should select questions to which they will always remember the answers.

The questions should be specific. General questions, such as the name of a pet, may be easily ascertained, for example from social media.

The questions should refer to something special in their life. If possible, the question should help trigger a positive memory and instil hope in them.

You will only have this procedure and its associated resources if you indicated that your organisation either has people who travel to hostile or insecure locations or if you indicated that your organisation has a permanent presence in overseas locations that are high risk.

Purpose: The Abduction Management Procedure details your organisation’s abduction management principles, responses, Proof of Life process, communicators, external actors, communications, and continuity activities.

This section details the key policy positions of your organisation.

You should adapt this section to better fit your organisation, work, and location, specifically reviewing (and where relevant amending) the bullet points related to non-payment and facilitation of ransom.

It is your organisation’s decision whether or not to pay or facilitate ransoms. This decision is extremely complex and involves multiple considerations including the following:

Your organisation’s ethical stance on ransom payments

Anti-terrorism legislation and sanctions

Different legal jurisdictions

If you are not certain of the positions to take regarding ransom payment and facilitation, we strongly recommend that you from Open Briefing.

This section details your organisation’s response to a suspected or confirmed abduction, including the actions that the CMT will take during the first hour, 1-2 hours, 2-6 hours, and 6-12 hours.

This section provides a flow chart representing the common sequence of events in an abduction situation. This is provided so that CMT members are clear on the possible events that will occur and the actions that should be taken in managing a suspected or confirmed abduction situation.

This section provides guidance, actions, and considerations in the event of the release of an abductee or the unsuccessful resolution of an abduction.

This section details why Proof of Life is an essential tool in abduction management, discusses the Proof of Life methods commonly available, and confirms the Proof of Life process.

The Abduction Management Procedure must remain confidential and restricted to your crisis management team and senior management. It should not be shared with others as it contains information that would be useful to abductors or other stakeholders involved in the case.

Further information is available in the guidance.

Purpose: The Abduction Incident Report Form should be used for all suspected or confirmed abductions. Each written report should include headline information, reporter information, incident information, and subsequent steps.

The Abduction Incident Report Form should be completed either by the Senior Person in the country where the abduction has taken place or by the Lead or Support on the CMT.

You will only have this procedure and its associated resources if you indicated that your organisation has a permanent presence in other countries.

Purpose: The Country Management Procedure details how your organisation’s programmes and offices in other countries can reduce their risk by developing and implementing a Country Security Plan. Each office or programme should complete their own specific Country Security Plan.

The Country Management Procedure presents the structure of the Country Security Plan, providing an overview of the following four documents that each country needs to complete:

Welcome Pack

Context Analysis

Country Risk Assessment

Finally, the Country Management Procedure also details when countries should update their Country Security Plans as follows:

For all locations. Whenever there is a significant change in the local context plus once a year.

For high-risk locations. Whenever there is a significant change in the local context plus either once per year, once every nine months, or once every six months depending on the risk rating.

Unless you intend to change either the structure of the Country Security Plan or the content of any of the four documents, it is not necessary to amend the Country Management Procedure itself.

Purpose: The Welcome Pack is the first of the four documents that make up the Country Security Plan. The purpose of the Welcome Pack is to provide useful security information and practical guidance for visitors.

The Welcome Pack should do the following:

Provide key facts about your organisation’s operations in the country

Detail the top threats and mitigation measures for the country

List what visitors need to do before, during, and after travel

To make it easier for staff to understand how to complete the Welcome Pack, we have provided examples directly in the document. However, it is vital that each overseas office or programme country adapts the Welcome Pack to better fit their organisation, work, and location. Under no circumstances should they accept the examples provided as these will not fit the local security context.

Purpose: The Context Analysis is the second of the four documents that make up the Country Security Plan. The purpose of the Context Analysis is to detail the context of both the country and your organisation in the country so that the office or programme can analyse the threats and vulnerabilities that arise from both.

The organisational context includes headline information, activities, human resources, reputation, offices, operating locations, and vehicle fleet (if relevant). The country context includes the sector, demographics, economy, education, politics, conflict, crime, security trends, religion and ethnicity, infrastructure and climate, communications and digital security, health, and increased exposure to risk. Each of these sections in the Context Analysis include a prompt to explain what information is relevant.

In each section, the person completing the document should outline how the factor affects the safety, security and wellbeing of your organisation and those who work on your behalf, focussing on specific threats.

Purpose: The Country Risk Assessment is the third of the four documents that make up the Country Security Plan. The purpose of the Country Risk Assessment is to help an office or programme in another country understand the threats present in that country so that they can develop appropriate measures to reduce risk.

To make this process simpler, the office or programme will need to complete the following five steps:

Identify the threats present in the country context by drawing on the Context Analysis.

Identify the reasons why your organisation’s operations and people in that country are vulnerable to each threat.

Score and describe the likelihood and impact of each threat affecting your operations or people.

To make it easier for countries to understand how to complete the Country Risk Assessment, we have provided guidance throughout the spreadsheet.

The Country Risk Assessment process can be somewhat subjective. As such, the process should be participatory and should include a range of internal stakeholders and not only senior managers. A great way of doing this is running a risk assessment workshop with people with different roles and at different levels of seniority.

Purpose: SOPs, Contingency Plans, and CMT is the fourth of four documents that make up the Country Security Plan.

To make it easier for staff to understand how to complete the SOPs, Contingency Plans, and CMT document, we have provided examples directly in the document. However, it is vital that each overseas office or programme country adapts the document to better fit their organisation, work, and location. Under no circumstances should they accept the examples provided, as these will not fit the local security context.

The document has three elements as follows:

Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). Detail the security measures that the office or programme in that country implements to reduce their risk. This allows them to be clearly communicated in writing to all relevant people in the country.

Contingency Plans. Detail the actions that the office or programme will take if the context changes. There are three contingency plans: scenario, programme, and medical.

Crisis Management Team (CMT). Identifies the people who are members of the country-level CMT.

Disclaimer: To the fullest extent permitted by law, Open Briefing will not be liable for any loss, damage or inconvenience arising as a consequence of any use or misuse of this resource.

Copyright © Open Briefing Ltd, 2020. Some rights reserved. Licensed under a .

Reviewed. An organisation’s risk appetite will fluctuate over time for many internal and external reasons.

Achieving our risk appetite. This section states that your organisation uses measurable indicators (present in your risk assessments and risk registers), allocates security and risk management strategies, and ensures that risk decisions are taken at the appropriate levels of management. All of this is detailed to evidence a systematic approach.

Contextual (e.g. social attitudes to your cause or organisation)

Phase 4 – Monitor

Look at the Scoring Definitions tab to decide the likelihood and impact scores (after implementing the mitigations) and enter either 1 (VERY LOW), 2 (LOW), 3 (MEDIUM), 4 (HIGH) or 5 (VERY HIGH) for each using the dropdown.

Identify if the risk is a ‘standing’ risk (e.g. safety and security) or a ‘temporary’ risk (e.g. a court case) using the dropdown.

Identify the risk management strategy your organisation will adopt (accept, avoid, transfer, manage) using the dropdown.

Develop further targeted measures to reduce the likelihood and impact of your organisation being harmed. Focus on reducing your organisation’s vulnerabilities (exposure).

Look at the Scoring Definitions tab to decide the remaining likelihood and impact scores (after implementing the targeted mitigations) and enter either 1 (VERY LOW), 2 (LOW), 3 (MEDIUM), 4 (HIGH) or 5 (VERY HIGH) for each using the dropdown.

Allocate a risk owner (the accountable), a risk manager (the responsible), and the deadline for achieving the target risk score.

Ensures that you continue to learn from past incidents that have been reported and managed.

Recording the information, options, and decisions made at the time in case of legal investigation at a later date.

Look at the Scoring Definitions tab to decide the likelihood and impact scores (after implementing the mitigations) and enter either 1 (VERY LOW), 2 (LOW), 3 (MEDIUM), 4 (HIGH) or 5 (VERY HIGH) for each, using the dropdown.

Send the risk assessment to the risk approver who will review and either approve or decline the travel. The latter could include asking for further mitigations to be implemented to reduce the risk to within your organisation’s risk appetite so that the travel can proceed.

The questions should not relate to potentially sensitive issues such as politics, religion, gender, sexual identity, or alcohol/drug use.

Crisis response (kidnap, ransom, and extortion) insurance

Organisational response capacity

Identify any entry and departure requirements and processes

List important and emergency contact details

Translate essential words and phrases

Develop mitigation measures to reduce the level of risk.

Score and describe the likelihood and impact of each threat affecting operations or people after the mitigation measures have been implemented.

Rights-based and humanitarian organisations must take risks to achieve change in the world. But in the face of attacks and harassment by governments, corporations, criminals, and armed groups, how do they take the right risks? The most-effective way to do this is through implementing a security risk management framework of policies and procedures.

‘Duty of care’ is your organisation’s obligation to provide a reasonable standard of care to those performing activities on its behalf that could bring them to foreseeable harm. The drivers behind duty of care are multiple and include legal and contractual requirements (including donor compliance) and your own organisation’s moral commitments. It is useful to break down the different elements of this definition for a deeper understanding:

Obligation. The drivers behind this obligation can be multiple, and no one driver is more important than any other. What is important is to recognise, set, and ultimately fulfil a standard to achieve the obligation.